Blog

April 15, 2021

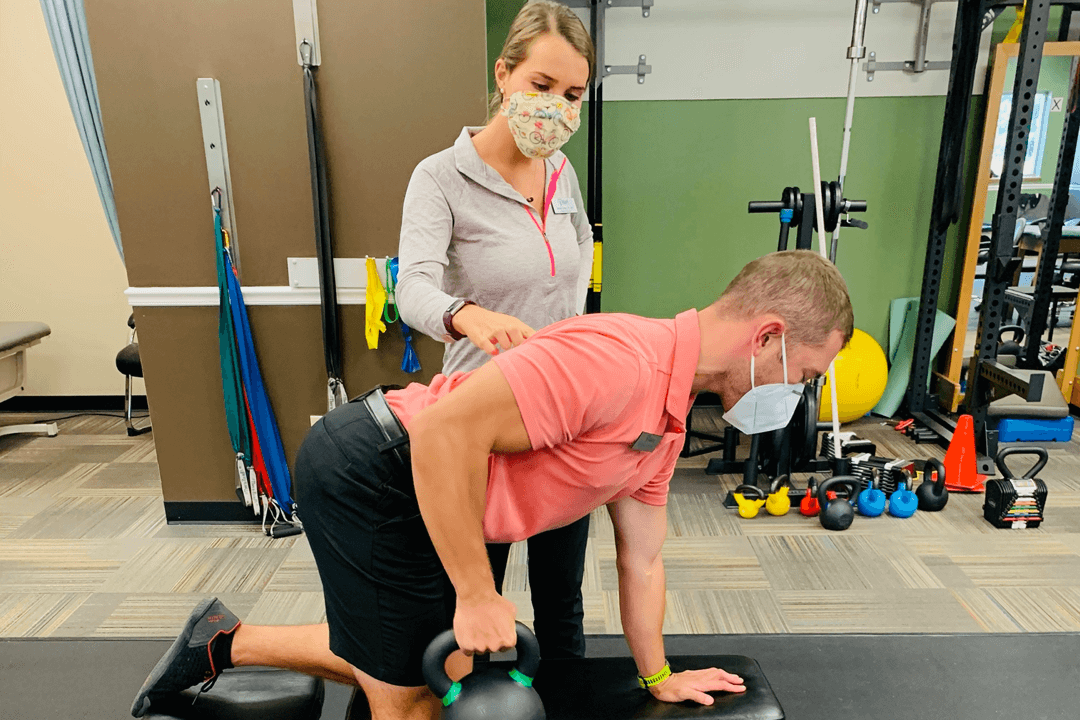

A concussion is actually considered to be a mild-moderate traumatic brain injury that temporarily impairs brain function. The brain is injured either through direct contact, such as a forceful blow to the head, or through rapid acceleration-deceleration, such as a whiplash injury. Common causes of concussion are contact sports (such as football, soccer, and hockey), falls, and motor vehicle accidents. Symptoms of a concussion may include headache, light/noise sensitivity, nausea/vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and memory loss. It is not necessary to experience loss of consciousness in order to be diagnosed with a concussion. When should I see my doctor? It is important to seek immediate medical attention if you experience the following “red flags”: Seizures Loss of consciousness or inability to awaken Lingering or progressive changes in hearing, taste, and/or sight Numbness and/or weakness in arms and legs Changes in behavior/increased irritation Unequal pupil sizes Persistent vomiting Symptoms that have significantly worsened or not improved after approximately 2 weeks What should I expect for my rehab? Most doctors will advise physical and mental rest for a few days immediately following the injury. It is then recommended that you gradually re-introduce both mental and physical activities, as long as there is no significant worsening of symptoms. Your physical therapist will likely guide you through a series of progressively graded cardiovascular/general conditioning exercises, strength training exercises, and eventually sport-specific activities (if applicable), all while carefully monitoring symptoms throughout to prevent aggravation of condition. They may also prescribe exercises to address dizziness, balance concerns, vertigo, and other general feelings of uneasiness. The process may be slow, especially if the injury was severe and the symptoms are significant, but it is critical not to re-injure the brain while it is healing.

By Nicholas Antonio, PT, DPT, CSCS

•

March 8, 2021

Whenever we find ourselves recovering from an injury, we tend to focus on the physical components of the recovery process. We direct our efforts towards targeting impairments such as stretching or strengthening a specific tissue, using ice or other modalities, or resting altogether. These factors are critical for a successful rehab experience, but they are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the total recovery picture. The tangible improvements we observe during healing, such as a cut scabbing over or a strained muscle feeling less painful or more flexible under load tend to be our go-to indicators that something is moving in the right direction and healing; but what are those behind the scenes factors that allow us to improve the quality and speed of the healing process? 1. Sleep Getting the recommended amount of sleep (7-9 hours per night) allows the body to recover appropriately. 2. Diet During healing, the body requires more total calories, protein, and vitamins to repair tissues. 3. Stress Increased cortisol levels in the body interrupts the inflammation process, resulting in slower healing. 4. Physical Activity Outside of Work Even if someone is active at their job, the body responds more favorably to exercise outside of the work environment. 5. Avoiding Tobacco Products Smoking tobacco products results in hypoxia (lack of oxygen) of the tissues, and oxygen is vital to healing. 6. Perception / Fear A person’s understanding of their condition is important. Fear of movement due to a diagnosis can contribute to chronic pain, despite an otherwise good prognosis. 7. Pessimistic Personality Attitude matters. Having a positive attitude contributes to better outcomes, while a poor attitude will result in the opposite. 8. Motivation Including home exercise compliance and in-clinic activity level, the time and effort you put into your recovery will help determine how fast you get better. Despite our profession beginning with “Physical,” your recovery is much more than that. Addressing as many of these factors as possible will allow you to return to doing what you love as soon as possible. Taking care of your whole self is the key

February 4, 2021

Dizziness may feel like vertigo (spinning), disequilibrium (unsteady), lightheaded, or motion sickness. Common causes of dizziness: Low blood pressure (Orthostatic hypotension) You may feel dizzy when you stand up quickly from a sitting or lying down position. If severe, this can cause you to pass out. How PT can help : Improving your cardiovascular fitness will help maintain a healthy blood pressure. Be sure to also drink enough water and have a healthy level of sodium in your diet to help with blood pressure. Inner ear problems (Vestibular system) Commonly referred to as Vertigo You may feel dizzy when you lie down on your back or turn your head to the side. Your vestibular system is in your inner ear and controls your balance. If this system isn’t working properly, you may feel dizzy, unbalanced, or nauseous. How PT can help : Specific exercises can be used to correct your inner ear problem. Visual processing issues You may feel dizzy or nauseous when you are in the car or move your head quickly Your eyes and your vestibular system work together. If your eyes aren’t moving how they should, this can affect your vestibular system and make you feel dizzy. How PT can help : Exercises can help correct your eye movements and get your visual system synchronized with your vestibular system. Muscle tension (Tension headache) Tension in your neck and shoulders can lead to headaches and feeling dizzy. How PT can help : Exercises and stretches can be used to normalize the tissue tension in your neck and shoulders. Your PT can also help you with maintaining good posture to prevent muscle tension. Brain injury (Stroke, TIA, traumatic brain injury) These injuries can affect the areas of your brain that control your balance. How PT can help : Exercises can help improve your balance by challenging both your muscles and your brain. Concussion You may feel dizzy, foggy, have a headache, or have neck pain after a head trauma How PT can help : Your PT can assess your baseline and help you return to activity and stimulation at an appropriate pace.

September 16, 2020

1.) Postural awareness Any position for an extended period of time is likely not going to be beneficial. In regards to the shoulder, if the scapula is in a rounded position and the humerus is in an internally rotated position, this can cause excessive compression on tendons of the rotator cuff. This posture is commonly observed with people who are sitting at a desk for extended periods or clicking a mouse at a computer screen all day. The fix - maintain proper seated and standing posture to eliminate unnecessary stress on the tendons of the rotator cuff. What is proper posture? Sit tall, shoulders back, chest up, lumbar support. 2.) Be aware of repetitive tasks Whether you are working in construction hammering nails, stocking shelves at a grocery store, or fixing up a room at your house, repetitive tasks (especially overhead) can be very irritating to the shoulder. Repeated movement can cause wear and tear to your rotator cuff tendons, and eventually result in more substantial injuries. Preventative measures- keep your shoulder in a stable position and take breaks when you can 3.) Strengthen and stabilize your shoulder girdle There are 4 main rotator cuff muscles, but over 10 more muscles that attach to your shoulder blade and humerus. It is essential to build up strength in your upper and mid back to maintain scapular stability, as well as perform exercises that force all of the muscles to co-contract and stabilize the head of the humerus in the socket of your shoulder blade. 4.) Maintain mobility in cervicothoracic spine Having restrictions in how your neck and upper back move can result in decreased range of motion at the shoulder joint, which in turn can result in pinching or poor use of the rotator cuff. 5.) Proper lifting mechanics Keeping your shoulder girdle in a stable and active position while lifting or carrying items of all weight is crucial to avoiding excessive stress on the smaller rotator cuff tendons. Tips - keep shoulder blade back and actively squeeze whatever you’re holding, this helps “turn on” the muscles throughout your arm and shoulder

February 5, 2019

Knee injuries commonly send people to the doctor's office. In 2010, more than 10 million visits to the doctor's office occurred due to knee pain and injury. Most of these visits were due to the same common problems. Knee injuries can often be treated at home, but some are serious enough to need surgical intervention. This article explains the anatomy of the knee, common knee injuries, and some of the treatment options. Ten common knee injuries The knee is a complicated joint. It moves like a door hinge, allowing a person to bend and straighten their legs so they can sit, squat, jump, and run. The knee is made up of four components - bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons. The femur, commonly known as the thighbone, is at the top of the knee joint. The shinbone, or tibia, makes up the bottom of the knee joint. The patella or kneecap covers the meeting point between the femur and tibia. The cartilage is the tissue that cushions the bones of the knee joint, helping ligaments slide easily over the bones and protecting the bones from an impact. There are four ligaments in the knee that act similarly to ropes, holding the bones together and stabilizing them. Tendons connect the muscles that support the knee joint to bones in the upper and lower leg. There are many different types of knee injuries. Below are 10 of the most common injuries of the knee. 1. Fractures Any of the bones in or around the knee can be fractured. The most commonly broken bone in the joint is the patella or kneecap. High impact trauma, such as a fall or car accident, causes most knee fractures. People with underlying osteoporosis may fracture their knees just by stepping the wrong way or tripping. 2. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) runs diagonally down the front of the knee, providing critical stability to the joint. Injuries to the ACL can be serious and require surgery. ACL injuries are graded on a scale from one to three. A grade 1 sprain is a mild injury to the ACL, while a grade 3 refers to a complete tear. Athletes who participate in contact sports such as football or soccer often injure their ACLs. However, contact sports are not the only cause of this injury. Improperly landing from a jump or quickly changing the direction of motion can lead to a tear in the ACL. 3. Dislocation Dislocating the knee happens when the bones of the knee are out of their proper placement and alignment. In a knee dislocation, one or more of the bones may slip out of place. Structural abnormalities or traumas, including car accidents, falls, and contact sports, can cause a knee dislocation. 4. Meniscal Tears When people refer to torn cartilage in the knee, they are probably talking about a meniscal tear. The menisci are two rubbery wedges of cartilage between the thighbone and shinbone. These pieces of cartilage can tear suddenly during sporting activities. They may also tear slowly due to aging. When the meniscus tears due to the natural aging process, it is referred to as a degenerative meniscus tear. With a sudden meniscus tear, a pop may be heard or felt in the knee. After the initial injury, pain, swelling, and tightness may increase over the next few days. 5. Bursitis Bursae are small fluid-filled sacs that cushion the knee joints and allow the tendons and ligaments to slide easily over the joint. These sacs can swell and become inflamed with overuse or repeated pressure from kneeling. This is known as bursitis. Most cases of bursitis are not serious and can be treated by self-care. However, some instances may require antibiotic treatment or aspiration, which is a procedure that uses a needle to withdraw excess fluid. 6. Tendonitis Tendonitis or inflammation in the knee is known as patellar tendinitis. This is an injury to the tendon that connects the kneecap to the shinbone. The patellar tendon works with the front of the thigh to extend the knee so a person can run, jump, and perform other physical activities. Often referred to as jumper's knee, tendonitis is common among athletes who frequently jump. However, any physically active person can be at risk of developing tendonitis. 7. Tendon Tears Tendons are soft tissues that connect the muscles to the bones. In the knee, a common tendon to be injured is the patellar. It is not uncommon for an athlete or middle-aged person involved in physical activities to tear or overstretch the tendons. Direct impact from a fall or hit may also cause a tear in the tendon. 8. Collateral ligament injuries Collateral ligaments connect the thighbone to the shinbone. Injury to these ligaments is a common problem for athletes, particularly those involved in contact sports. Collateral ligament tears often occur due to a direct impact or collision with another person or object. 9. Iliotibial band syndrome Iliotibial band syndrome is common among long-distance runners. It is caused when the iliotibial band, which is located on the outside of the knee, rubs against the outside of the knee joint. Typically, the pain starts off as a minor irritation. It can gradually build to the point where a runner must stop running for a period to let the iliotibial band heal. 10. Posterior cruciate ligament injuries The posterior cruciate ligament is located at the back of the knee. It is one of the many ligaments that connect the thighbone to the shinbone. This ligament keeps the shinbone from moving too far backward. An injury to the posterior cruciate requires powerful force while the knee is in a bent position. This level of force typically happens when someone falls hard onto a bent knee or is in an accident that impacts the knee while it is bent. When to see a doctor If knee pain becomes chronic, is severe, or lasts for more than a week, a person should consult a doctor. It is important to see a doctor if there is a reduced range of motion in the joint or if bending the knee becomes difficult. In cases of blunt force or trauma, a doctor should be seen immediately after an injury has occurred. Treatment options Treatment will vary based on the cause of the knee pain and the specifics of the injury. In cases of strain or overuse injuries, rest and ice will typically allow the knee to heal over time. Treatment may also involve managing pain and inflammation with medication. In most cases, a person will need to rest for a period of time. Tears or other trauma-induced injuries may require bracing, popping the knee back into place, or surgery. In the case of surgery, a person will likely not be able to use the knee after the procedure and may need either crutches or a wheelchair while recovering. In some cases, physical therapy may be needed to help a person regain movement and strength in their knee and leg. Prevention Preventing knee injuries is not always possible, but a person can take precautions to reduce the risk. For instance, people who run or play sports should wear the appropriate shoes and protective gear. In cases of iliotibial band syndrome and overuse injuries, a person may want to consider reducing the number of miles they run. Certain exercises also help strengthen the smaller leg muscles, which may help prevent injury. Finally, stretching before and after exercise can help prevent injury to the knees. Proper nutrition, especially for athletes, is also important. Protein, calcium, and vitamin D are essential for maintaining healthy bones, muscles, and ligaments.

February 12, 2017

Cryotherapy is a fancy word for the non-fancy practice of “putting ice on someone”. We often think about ice decreasing tissue damage, swelling and pain after injury, but does it actually achieve this? Is ice useful in acute injuries? If it is, how long should ice be applied? Should you really eat the frozen peas or chicken nuggets you used to ice your ankle? All these questions and more (or less) are answered here from the latest research on ice (see below for references). Does ice application reduce swelling? Ice application reduces the tissue temperature, which decreases cell metabolism in the area surrounding the injury, and decreases the amount of secondary damage in the tissue surrounding the injury. Animal studies demonstrate a significant decrease in cell metabolism when tissue temperature is lowered to 5 to 15 degrees. There is level 2 evidence that ice DOES NOT reduce swelling . The main effect of ice is to decrease nerve conduction velocity, thereby reducing pain from surface tissues. This allows your patient to perform their exercises and mobilise the area, which has a secondary effect of reducing swelling. What is the best way to apply ice? Not all ice packs are created equal. For decreased nerve conduction velocity, we are trying to achieve a tissue temperature of 10 degrees. Frozen peas or gel packs help yourself and your patients to avoid the mess of cleaning up slippery pools of water all over the floor, which is a wonderful thing. Is it all good news on the frozen peas front though? Crushed ice will achieve our goal skin temperature within 5 minutes, however other types of icing eg gel packs, frozen peas do not get the skin temperature lower than 13 degrees, which unfortunately is not low enough to have an adequate effect on nerve conduction velocity. Therefore the best way to apply ice is crushed ice in a plastic bag applied directly to the skin, followed by quickly getting someone nearby to mop up the mess you have just created. How long should we apply ice? We have all probably used or recommended at one point in time the application of ice for 20 minutes on every hour, or 20 minutes on/20 minutes off. Using crushed ice, our skin temperature can be reduced to our goal temperature within 5 minutes. If the goal is to reduce nerve conduction velocity and pain, and allow performance of exercise/mobility, this is enough. If you are trying to achieve a decrease in tissue temperature at the injury site, the depth of the injured tissue and the amount of bodyfat the patient has are also factors in the length of time that ice is applied. If you have an injured athlete that is very lean, with an injury close to the surface eg lateral ankle ligament injury, you may achieve this with shorter periods of ice. If you have a patient that has a deeper injury eg within the hamstring muscle belly, and has some fat overlying the area, it will require much longer application of ice to reduce tissue temperature, and you may not even be able to reduce the temperature of your targeted tissue at all. 20 minutes of ice application in this instance is unlikely to be enough. Should we use padding or towels with ice application? Padding is normally used to protect the skin from frostbite and ice injury. In the 35 studies that have applied ice directly to the skin, there have been no recorded skin injuries in clinical application. The only injuries have occurred are with application for 60 minutes at a time or if the patient has fallen asleep. Before applying ice, as with all treatments, you need to check the patient does not have any contraindications or precautions to ice application eg allergy to cold. If crushed ice is applied directly to the skin, it is not comfortable, but it is very effective. If it is applied over bandages or dry towels, icing is ineffective. Check the skin for adverse or allergic reaction after the first minute, and every five minutes. Contraindications and precautions to ice Contraindications to ice therapy include: Active deep vein thrombosis or thrombophlebitis Areas near a chronic wound Cold hypersensitivity eg Raynaud’s, cryoglobulinema, hemoglobulinemia Cold urticaria (cold allergy or hypersensitivity) Impaired circulation Over regenerating nerves Tissues affected by tuberculosis Haemorrhaging tissue Untreated haemorrhagic disorders Areas with impaired circulation Precautions to ice therapy include: People with cardiac failure People with hypertension Areas of impaired sensation that prevent people form giving accurate and timely feedback Infected tissues Damaged or at-risk skin References Algafly, A. A., & George, K. P. (2007). The effect of cryotherapy on nerve conduction velocity, pain threshold and pain tolerance. Br J Sports Med, 41(6), 365-9; discussion 369. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.031237 Bleakley, C. (2004). The Use of Ice in the Treatment of Acute Soft-Tissue Injury: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(1), 251-261. doi:10.1177/0363546503260757 Bleakley, C. M., McDonough, S. M., MacAuley, D. C., & Bjordal, J. (2006). Cryotherapy for acute ankle sprains: a randomised controlled study of two different icing protocols. Br J Sports Med, 40(8), 700-5; discussion 705. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.025932 Bleakley, C. M., O’Connor, S. R., Tully, M. A., Rocke, L. G., Macauley, D. C., Bradbury, I., . . . McDonough, S. M. (2010). Effect of accelerated rehabilitation on function after ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 340, c1964. doi:10.1136/bmj.c1964 Ewell, M., Griffin, C., & Hull, J. (2014). The use of focal knee joint cryotherapy to improve functional outcomes after total knee arthroplasty: review article. PM R, 6(8), 729-738. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.02.004 Kerkhoffs, G. M., van den Bekerom, M., Elders, L. A., van Beek, P. A., Hullegie, W. A., Bloemers, G. M., . . . de Bie, R. A. (2012). Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: an evidence-based clinical guideline. Br J Sports Med, 46(12), 854-860. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090490 Malanga, G. A., Yan, N., & Stark, J. (2015). Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injury. Postgrad Med, 127(1), 57-65. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=25526231 Mitchell, A. C., & Thain, P. (2011). The Effect of Intermittent Ice Application on Dynamic Postural Control. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25, S62-S63. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/2011/03001/The_Effect_of_Intermittent_Ice_Application_on.98.aspx Prado, M. P., Mendes, A. A., Amodio, D. T., Camanho, G. L., Smyth, N. A., & Fernandes, T. D. (2014). A comparative, prospective, and randomized study of two conservative treatment protocols for first-episode lateral ankle ligament injuries. Foot Ankle Int, 35(3), 201-206. doi:10.1177/1071100713519776 Williams, E. E., Miller III, S. J., Sebastianelli, W. J., & Vairo, G. L. (2013). ORIGINAL RESEARCH. COMPARATIVE IMMEDIATE FUNCTIONAL OUTCOMES AMONG CRYOTHERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS AT THE ANKLE. International journal of sports physical therapy, 8(6), 828-837. Original Article By Clinic Edge

July 5, 2013

Patients who suffer from back and neck injuries may need to undergo several different types of corrective care exercises, many of which might not have the positive results patients are seeking. While medical professionals may utilize a trial-and-error approach to these corrective care exercises, a new study reveals that physical therapists may be able to use a clinical prediction rule (CPR) to determine which patients are most likely to benefit from cervical traction and exercise. Researchers suggest that this CPR will make it much easier for clinicians to design effective exercise treatments that could have a positive impact on patients suffering from neck pain. In a study released by the Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, eighty patients who suffered from neck pain received a standard examination and then underwent six sessions of cervical traction and strengthening exercises over the course of three weeks (sessions were held twice weekly). At the end of the study, patients were asked to assess their perceived recovery. Out of sixty-eight patients, 30 were reported to have a successful outcome, in which they reported their neck pain to be “a great deal better” or “a very great deal better.” Throughout the study, researchers carefully examined patients to determine an ideal CPR assessment. The study concluded that clinicians could predict which patients will experience positive benefits from cervical traction and exercises via the five following variables: Patients reported peripheralization with lower cervical spine mobility testing; Patients demonstrated positive shoulder abduction; Patients were 55 years or older in age; Patients demonstrated positive upper limb tension tests; and Patients demonstrated positive neck distraction tests. Using these five variables, clinicians can help determine if patients could potentially experience positive therapeutic outcomes associated with cervical traction and related neck exercises. Additionally, researchers concluded that having at least three out of the five CPR variables increased the likelihood of success from cervical traction from 44 to 79.2%. Patients who demonstrated four out of five CPR variables have a likelihood of success from cervical traction increase to 94.8%. While several studies need to be conducted to strengthen the arguments of this new CPR model, the conclusions have successfully demonstrated that clinicians can predict with increasing success which patients could benefit the most from cervical traction and other related exercises. As reported in Volume 38, Number 4, pp 300–307 of Spine.

June 4, 2013

The ankle is one of the most fragile parts of the body; therefore, it’s no surprise that many major sports injuries revolve around the ankle. Ankle sprain has accounted for 76.7% of injuries, which is followed at a distant second by fractures (16.3%). Sports like basketball and soccer have the highest risk of ankle injuries, as these sports can place significant stress on the ankle. It’s estimated that when an ankle injury occurs, the chance of re-spraining the ankle increases by a whopping 80%. Therefore, determining an athlete’s return to sports after ankle injury is a critical decision that many clinicians must make. Fortunately, there is a barrage of tests that can help a clinician determine when an athlete is ready to return to sports after an ankle injury. In a recent journal article published in the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine, researchers outlined which parameters must be examined – both physical and psychological – in order for a clinician to decide if an athlete is ready to return to sports. Researchers argued that a current lack of evidence-based guidelines make it difficult for clinicians to determine with confidence when an athlete can return to the game. After researching several tests via primary literature searches, researchers concluded that clinicians could utilize the following tests to determine readiness: The dorsiflexion lunge test; The star excursion balance test; The agility T-test; and Sargent/vertical jump test. These physical functional tests play a crucial role in determining an athlete’s readiness because it assesses a range of critical motions, including motion, balance, proprioception, agility and strength. Researchers argue that these indicators offer the best demonstration of an athlete’s ability to play on the court without increasing his or her risk of re-sprain or re-injury. Researchers also point out that clinicians should prioritize psychological evaluations as much are primary functional ones. Trained athletes who make their living via physical activities may be frustrated by the amount of recovery and therapy that’s involved in healing an ankle injury. Therefore, clinicians should ensure that athletes truly understand the degree of rehabilitation that must occur before an athlete should return to their sports of choice. As reported in the October 2012 of American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine.